Ukraine is a country that is on everyone’s lips these days, unfortunately for the wrong reasons. As a student, I spent a month in the Black Sea port of Odesa (then spelled Odessa) in the summer of 1996 and wrote an article about my experience when I got home. It was never published but, 29 years later, I’ve adapted it to publish here on my blog:

The old lady threw me a bewildered, half angry glance as I trod heavily on her foot in a desperate attempt to get off the over-crowded tram.

I’d muttered something in Russian in the process and it wasn’t until I was standing in the road again that I realised that I’d said ‘thank you’ instead of ‘sorry’.

Oh well, this was only my second week in Ukraine, and I didn’t speak Russian (or Ukrainian, for that matter). What do you expect?

I still have to work out what exactly I was expecting myself when I signed up to teach English for a month in a summer school in Odesa, in August 1996.

I was approaching the end of my first year at University (studying French and German) when I saw a poster in the student union offering students the chance to teach English in Odesa over the summer.

You paid a company (that later went into liquidation…still, that’s another story!) and they organised your flights, a summer school for you to teach at, a host family to stay with, activities/excursions/Russian classes in the afternoons (they didn’t happen) and supposedly some teacher training (that also didn’t happen).

In return, you got to spend a month in this beautiful city on the shores of the Black Sea, known as the Pearl by the Sea, learn some Russian (which was everyone’s first language in Odesa – also known as Odesan Russian), experience a different culture and generally have your eyes opened to how people were living in the post-Soviet era.

My great-grandfather was from Odesa so, although I didn’t speak any Russian, it seemed a good way of spending some of the long university summer holidays.

I probably should have gone to France or Germany, to practise the languages I was actually studying, but I’d caught the travel bug and wanted to go somewhere completely new.

However, when we arrived – I flew out there with two other student teachers – we were met at the airport by our company’s Ukrainian contact, Sacha.

Sorry, he said, there was actually going to be no teaching as they already had enough teachers (you’d have thought they might have foreseen this, but hey).

Because of this there would also be no programme of activities or excursions, or Russian classes (nothing extra that we’d paid for, in other words).

Naturally we were incredibly disappointed, but even though they offered to send us straight home again, we stood our ground and insisted they found us some kind of teaching job.

So they buddied us up with the teachers who were already there and we ended up being sort of classroom ‘assistants’. I was teamed with a girl from Dundee who’d already been in Odesa for a few weeks and we had a class of around eight students, whose ages ranged from under 10 to teenagers, and who came from all over Ukraine and Russia.

I actually remember very little about the classes, apart from the fact that the youngest child, a boy, spoke the best English, and there was a girl there who came from Murmansk in the far north of Russia, inside the Arctic Circle.

After classes ended at about midday, we’d invariably go and join our fellow English teachers, a motley bunch from all over the UK for a pivo (beer) in a local café and then we’d either head to the beach, or home to our respective host families.

My host family

There wasn’t much to do at “home” though. I was staying with a family in their one-bedroom flat, located several floors up in a Soviet-style apartment block.

They were incredibly kind and hospitable. The father moved out – I think he slept in his office – so I could have the single bedroom to myself during the month I was there. The mother and 22-year-old student daughter Ilyena (whose English when I arrived was marginally better than my pathetically few words of Russian – by the time I left, however, she was almost fluent) shared a sofa-bed in the sitting room.

There was a balcony only big enough for drying clothes on, a lounge with a TV and a huge picture of a forest covering one of the walls, a small kitchen, and a bathroom with a toilet and bath, but no functioning wash basin.

At least, it wasn’t connected to a pipe – which I only discovered the first night when I turned on the tap and water splashed all over the floor.

At that time, no private homes had running water from midday for five hours and from midnight until the morning.

When the water was off, the family kept the bath filled up with water which they used for flushing the toilet and washing clothes.

Nowhere, not even the hotels, had hot water at all during the summer, but it was so hot I was glad to have cold showers, when there was running water.

A city falling to pieces

Odesa’s centre, with its French and Italian-style buildings, tree-lined boulevards and squares, was beautiful, but seemed to me to be completely falling to pieces.

There was no money to be had, apparently, unless you were a “businessman”, whatever that meant. I was told, for example, that a secretary working in a private firm earned on average the equivalent of £65 per month, which was considered a good salary.

Not many people had cars – all the rather dilapidated buses and trams were free, with the inevitable result that they got so crowded I often found myself fighting for a space on the handrail, let alone somewhere to sit.

A night out? Think again!

As a 20-year-old student, I’d assumed/hoped there would be some kind of nightlife there, but niet! It was considered too dangerous for a woman to go out at night; if you did, your mother usually accompanied you.

I asked Ilyena why they didn’t just take taxis: that was also a no-no, she said. Real taxis were few and far between; it was the norm to flag down a passing car, agree a price with the driver and then pay him on arrival at your chosen destination.

There was also a serious alcohol problem – ½ litre of Ukrainian vodka cost as little as 70p – but women, Ilyena included, preferred a more chic, fizzy wine they called “champagne”. I did, however, bring home a couple of bottles of vodka to enjoy with my Uni flatmates in our student digs.

Another souvenir I took back with me was a set of Russian dolls (literally!) that I bought in a flea market there. It’s funny, but I don’t remember there being a Ukrainian equivalent.

Given the absence of organised activities, I had plenty of time for the beach, and swimming in the Black Sea – especially after I’d exhausted the city’s museums, where I couldn’t understand anything anyway as the explanations were all, understandably, in Cyrillic.

A paradise on the city edge

I started to spend more time with Laura, a Glaswegian English teacher I’d flown out with, who was staying with an older couple, Galina and Valerii, in a country cottage near the beach somewhere on the edge of the city.

I remember a long, sweaty tram ride to get there from the school, walking past what looked like a disused sanatorium (a throw-back to the USSR?) in the woods to get to the beach, cooling off in the sea, then going back to Galina’s place to sit on her vine-covered terrace and eat home-grown apricots from her garden.

Galina had a rustic shower at the front of her garden where we freshened up post-beach (I don’t remember her having any problems with running water).

I loved spending my afternoons there and often returned somewhat reluctantly to the inner-city flat I was accommodated in, but looking back maybe it wasn’t so bad. We’d all have dinner together, Ilyena and I would chat about our days and we’d watch Dynasty badly dubbed in Russian.

Food, glorious food

I enjoyed the meals that Ilyena’s mother used to cook, although I have to admit I did get a bit tired of having borscht every day for starters – but she made wonderful apple fritters, served with soured cream.

She spoke no English but we communicated through sign language and I did pick up a few words of Russian.

I knew when it was dinnertime, for example, because she used to mime eating, and say kushet? which I soon learnt meant eat? – and when Ilyena wasn’t at home I used to ask her mum gdye Ilyena? = where is Ilyena? I probably didn’t understand the answer, however.

One of the things I most loved eating in Odesa was watermelon – it seemed a massive novelty to me as we never ate it in England – so much so that on my last day the family presented me with a huge watermelon to take back to London.

I’m sure it more than doubled my luggage allowance. It even went through a security check at the airport.

But once on the plane, I was (rightly) told to take it out of the overhead locker – in case it rolled out and fell on someone’s head, no doubt – and keep it under the seat in front of me.

Plans to travel

Before I arrived in Ukraine, I’d hoped to do some travelling beyond Odesa and see some of the country – visit the capital, Kyiv, even. However once there, I realised that unless you bought your train tickets three weeks in advance, you’d find the Mafia had already bought them, to resell at a vast profit.

In the end the only time I left the city was to spend a weekend at my host family’s dacha, the Ukrainian equivalent to the British summer home.

Ilyena, her parents, Laura, who Ilyena had also become friendly with, and I piled into their tiny car and drove to a modest plot of land near a lake about 30km outside Odesa. There, the family had built a tiny room at the top of a tall ladder, with no room for anything in it other than a large mattress. There must have been something underneath this room, but all I remember was an outside kitchen and toilet.

Ilyena, Laura and I shared the room, while the parents slept in their car. It was my last weekend in Ukraine, and it was an unforgettable experience.

Although it was 29 years ago now I still remember the delicious lamb dinner Ilyena’s parents cooked for us on the outside stove/fire, washing it down with red wine and then walking to the lake when it was dark and just laughing and laughing.

I took photos but not a single photo from my Odesa trip came out, for some reason – this was long before digital cameras – so sadly I have no photographic evidence of me ever having been there.

Ilyena and I exchanged letters for a while after I left Odesa, but then we inevitably lost touch. I’ve often thought about her and her family in the years since, and how they’re doing – especially in the last three years.

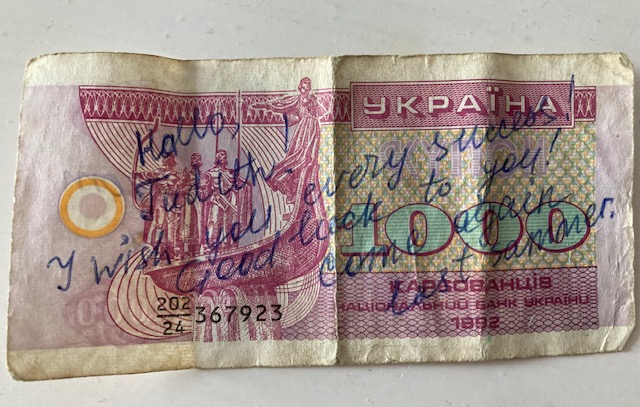

I wish I had a way of getting in touch with her but of course this was before mobile phones or social media, and I don’t remember her even having an email address.

I’ve also lost touch with Laura, who said she’d send me copies of the photos she took of us in Odesa – but she never did. I particularly wanted to see some of those from our weekend at the dacha. Luckily, I still remember some things about it.

My time in Odesa was a long time ago, and when I see pictures from Ukraine in the news now I can’t believe I was ever there. I just hope this war will be over soon.